Cordless 3D Scanning on the Horizon

Creaform’s HandySCAN 3D, a metrology-grade scanner for handheld use. Image courtesy of Creaform.

Latest News

August 1, 2017

Usually, you expect handheld devices to be portable and mobile. But there are some limits to this portability when it comes to professional 3D scanners. Many scanners require you to keep the device attached to a powerful computer during the scanning operation. The device relies on the processing power of the computer to align the partially scanned images into a cohesive whole. It also borrows the computer’s display to show you the scan progress, scan quality and other cues.

The cord is not a major hindrance if you need to scan something small or something you can easily relocate. But if you need to scan a classic car that cannot be removed from a showroom, a piece of heavy machinery in a tight corner or a statue permanently installed in a park, the tethered scanner and the accompanying computer may demand ingenuity and workarounds.

“The request for cordless scanners comes quite often,” says François Leclerc, product manager for scanning and measurement equipment developer Creaform.

Creaform’s HandySCAN 3D, a metrology-grade scanner for handheld use. Image courtesy of Creaform.

Creaform’s HandySCAN 3D, a metrology-grade scanner for handheld use. Image courtesy of Creaform.“The industry does want a cordless scanner,” agrees Joel Martin, product manager for Hexagon’s Manufacturing Intelligence (MI) division.

In the consumer and prosumer space, a handful of cordless scanners have recently appeared. But with metrology-grade or professional-grade scanners for inspection, some vendors say what is required to go cordless at present may be too high a compromise in the scanner’s capability, weight and cost.

Reverse-Engineering vs. Inspection

3D scanning can be divided into two distinct workflows: reverse-engineering and inspection. With reverse-engineering, users scan an object to digitally capture its shape so that it can be modified, refined and reproduced. This approach may be employed by artists who want to create something that mimics a natural object or a living organism; engineers who need to manufacture a legacy component that has no digital record and architects who need to virtually examine an existing site or structure for improvement options. Makers, hackers and tinkerers with DIY (do it yourself) projects also employ this approach. Thus, the pool of users in this segment is rapidly growing and the wide price range and options reflect that.

Without an attachment to a computer, the cordless Leo allows you to carry the device into tight corners with limited room. Image courtesy of Artec 3D.

Without an attachment to a computer, the cordless Leo allows you to carry the device into tight corners with limited room. Image courtesy of Artec 3D.With inspection, users typically use professional, metrology-grade scanners to capture an object’s shape to verify its fidelity to the original concept—or its deviation from it. Aerospace and automotive engineers, for example, use this approach to ensure the parts and components manufactured match the original design specifications as recorded in 2D and 3D CAD files. The accuracy required for inspection is generally much higher than what’s needed for reverse-engineering or simple digitization. Scanners of this caliber usually have a higher price tag than those in consumer and prosumer markets.

Accurate Enough?

Scanners generally work by emitting light beam patterns toward the target object and collecting the beams bouncing back. Based on the pattern deformation resulting from the target’s curvature, the scanner (to be precise, the software that comes with the scanner) can reconstruct the object’s 3D geometry in point clouds.

“A consumer-grade scanner is fine if you’re a tinkerer and just want to capture something’s shape. But if you’re in aerospace and you want to make sure the component you install fits inside a tight assembly, you need something much more,” says Leclerc. “Normally, the scanner captures the target’s shape in point clouds, then converts it to STL (STereoLithography format). Our scanners build the surface model in real time.”

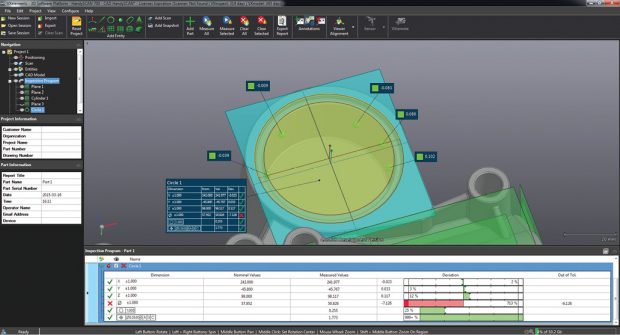

With 3D scanners, the software plays an important role to help you assemble the data from different scans into a single model. Shown here is VX Elements software from Creaform. Image courtesy of Creaform.

With 3D scanners, the software plays an important role to help you assemble the data from different scans into a single model. Shown here is VX Elements software from Creaform. Image courtesy of Creaform.“Consumer-grade scanners are good for someone who wants to scan their face or body and 3D-print an avatar. They also work well for those who want to capture some real-world structures and reuse them as game environments, for example,” says Martin. “But metrology-grade is what you use to measure carbon composite parts in passenger jets. This is where you don’t just want the general shape of the part, but you want the part digitized with all its fine details, like holes, slots, edge lines and cut lines. This is where you want things to be highly accurate, not reasonably accurate.”

Creaform offers a number of handheld scanners: Go!SCAN 3D (0.9 kg, 2.05 lbs.), HandySCAN 3D (0.85 kg, 1.9 lbs.) and MetraSCAN 3D (1.38 kg, 3 lbs.). Pricing starts at $25,000. The Go!SCAN 3D offers accuracy up to 0.1 mm (0.004 in.)—essentially a measurement thinner than human hair. HandySCAN 3D’s accuracy is up to 0.04 mm (0.0016 in.). The MetraSCAN 3D’s accuracy is up to 0.030 mm (0.0012 in.).

They come with the company’s VXmodel software, which includes mesh editing, scan data alignment, surface generation and CAD transfer tools. Of the three, the Go!SCAN 3D is considered an entry-level device for professional work, according to Leclerc.

Hexagon’s MI division offers a number of portable scanners, including the Leica T-Scan 5 and the Leica Absolute Scanner. The hardware works with Hexagon’s PCD-MIS (for measurement), SpatialAnalyzer (for scan data alignment and deviation analysis) and 3DReshaper (for point-cloud processing) software products.

Going Cordless

What makes Artec 3D’s handheld scanner Leo much better than its predecessors is not what’s added to it but instead what’s missing: the cord. The company’s previous handheld scanners, Eva and Spider, work with cords attached to PCs. Leo is the first to ditch the cord.

Artec 3D straddles several different markets. It caters to the industrial design and manufacturing, healthcare and art sectors. It also operates the avatar-printing service Shapify Me. The company launched Leo at a press event hosted by GPU (graphics processing unit) maker NVIDIA in March. “Artec Leo embodies the next wave of the 3D scanning industry,” says Artyom Yukhin, president and CEO of Artec 3D. “Our goal is to make professional 3D scanning as easy as shooting video for any industry, and Artec Leo is the next big step in achieving that goal.”

Leo has a built-in touch-panel screen. NVIDIA Jetson serves as the scanner’s own internal computer. It features a quad-core ARM Cortex CPU and NVIDIA Maxwell GPU with 256 NVIDIA CUDA Cores. It comes with a touch-panel display that can also be mirrored to another PC screen wirelessly. The scanned data is saved on a 256GB solid-state drive. You can, therefore, complete the scan session on the device before offloading the data to a PC or server back at the office. You have the option to extend the storage with a microSD card.

“The fact that Leo can scan wirelessly and visualize the process onboard is the real advantage,” says Andrei Vakulenko, chief business development officer at Artec 3D. “With the onboard screen, you can immediately see which section of the object you are scanning, while at the same time ensure that the device is held at the right distance from the object. Prior to this, using a handheld 3D scanner was a little like pointing a video camera at the object and, instead of looking through the viewfinder, holding another piece of equipment to look at the target—all this while walking around the object. Using a separate screen that is not embedded in a scanner requires a lot of coordination, which is far from intuitive. With Leo, the scanning process has become much simpler and therefore faster as well. The built-in screen also means you don’t have to 3D scan one-handed, so you can use two hands to decrease fatigue from weight.”

Leo works with Artec Studio 12 Software for scan-processing software. The program includes an Autopilot mode, which guides beginning users through the scan process. Version 12 allows direct export to Geomagic Design X and SOLIDWORKS 3D CAD programs. Leo weighs 1.8 kg (4 lbs.). Its 3D point accuracy is up to 0.1 mm. Pricing begins at $25,000.

The Added Weight of Mobility

Making a scanner cordless means adding a built-in power source, enough processing CPU and GPU power to align the acquired data locally, and a small screen to monitor the scan progress. All of these add weight to the device, which has ergonomic implications in routine, long-term use.

“If the operator has to hold the scanner for more than five or 10 minutes, if it’s their job to scan for four or six hours a day, then the device’s weight becomes a hindrance,” says Martin. “We’ve looked at developing a cordless scanner. We do a tremendous amount of work in R&D to reduce the excess weight from our products. But as soon as we add the battery, it gets heavy. It’s the photons-out, photons-back operation that really limits the metrology-grade scanners’ portability.”

At 4 lbs., the cordless Leo from Artec 3D weighs nearly twice as much as Creaform’s Go!SCAN 3D (2.5 lbs.) or Hexagon MI’s Leica Absolute Scanner (2 lbs.). For long-time usage (say, scanning a vehicle or a plane), the added weight could result in user fatigue sooner. Leo’s accuracy is up to 0.1 mm, the same as Creaform’s Go!SCAN 3D.

“In metrology-grade scanners the cameras are working at about 60 FPS (frames per second). There’s a lot of data to transfer. And the cord is more reliable than a Wi-Fi signal,” says Leclerc. “That’s why we power it with a cord right now, and that’s the reason the scanner doesn’t need a battery pack to operate.” In some Creaform scanners, the Wi-Fi-enabled remote screen option lets you project the screen to a mobile tablet, thus giving you some mobility despite the tethered setup.

Blurring the Line

Scanner technologies—such as battery, display and mobile processors—“are moving in the right direction at an aggressive pace,” notes Martin. Therefore, lightweight, cordless metrology-grade scanners that are currently infeasible may soon begin to appear.

If the precedence set in 3D printing is an indicator of what could happen to 3D scanning, we might soon see the margins blurring between the consumer and professional segments. “When the two markets converge, you’ll start to see really interesting products,” says Martin.

More Info:

Hexagon Manufacturing Intelligence

Note: Some portions of this article appeared previously as part of the blog post titled “Artec 3D’s Handheld Scanner Leo: Finally, You Are Free to Roam.”

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Kenneth Wong is Digital Engineering’s resident blogger and senior editor. Email him at [email protected] or share your thoughts on this article at digitaleng.news/facebook.

Follow DE