Latest News

June 21, 2018

By Miles Parker

The acronym DFM, for design for manufacture, has meant more than a few things during the post- WWII industrial era. It has always been associated with Producibility Guidelines, which are concerned with proper draft angles and ways to generally make manufacturing easier and faster. DFM also blends with Lean strategies and an array of best practices for casting, molding, machining and more. However, contemporary DFM is also a powerful purchasing and business tool.

What distinguishes advanced DFM from previous efforts is its scientific focus, use of quantitative data, and holistic approach to both production and design issues. Embodied in software rather than shop floor binders, it quickly compares competing processes and materials, optimizes manufacturing sequences and appraises estimates—the hardened cost profiles of which result when engineers, managers and suppliers negotiate and then, ideally, innovate.

A particularly valuable strength of DFM is that it’s constructed to allow team members to work off “whiteboard” drawings of rough geometric ideas or early “napkin” sketches, independent of CAD if necessary, in order to flesh out ideas before human resistance sets in and formal modeling efforts discourage revision. Following are two examples that emphasize the benefits of early analysis and DFM as a business process.

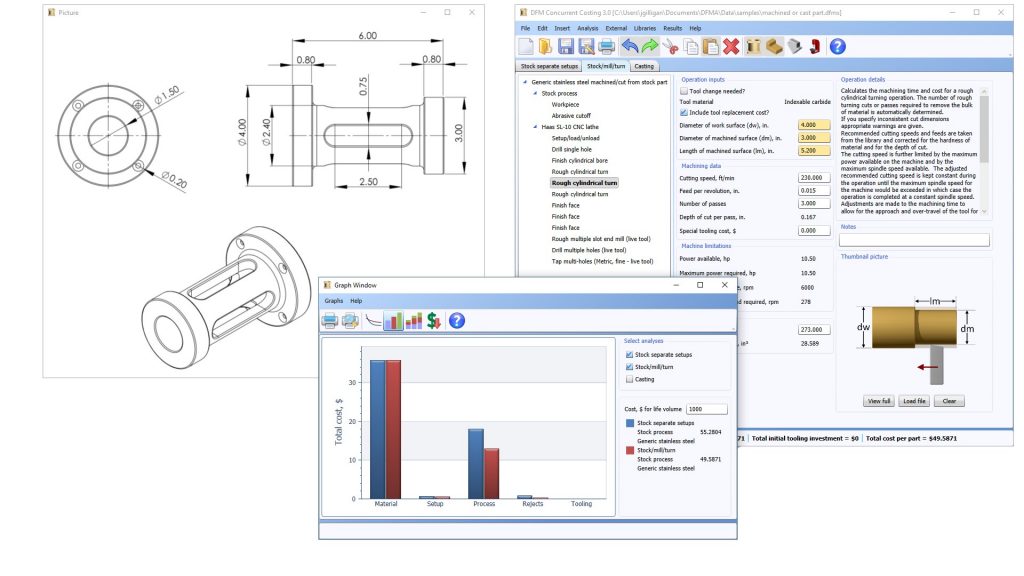

Power Tools and Power Costing

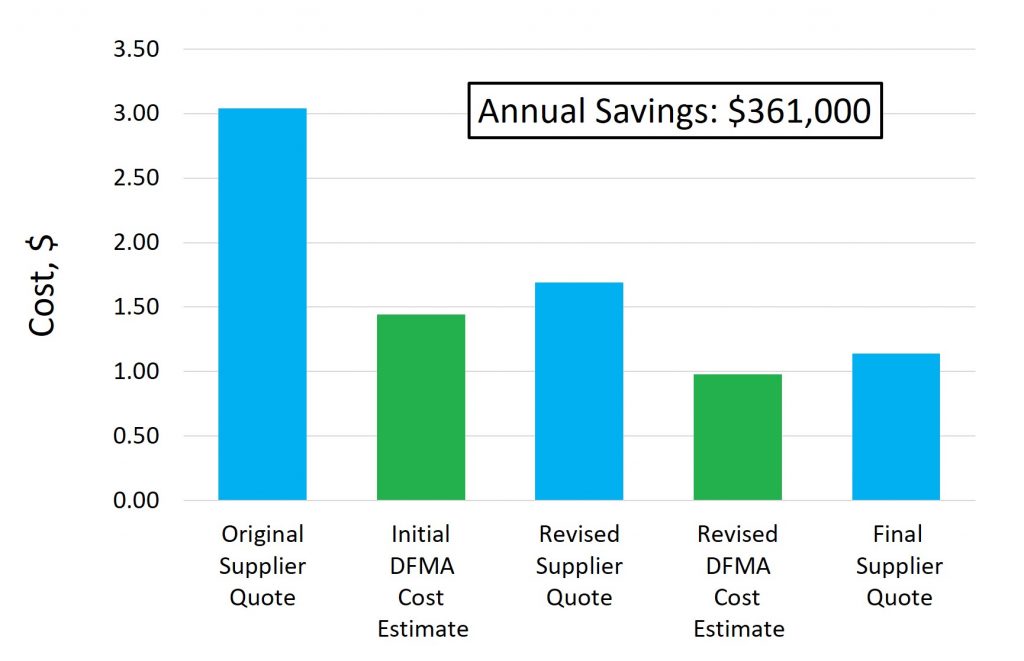

Even the smallest projects using quantitative DFM can pay big returns. A global manufacturer of power tools and home products decided to closely review a foreign bid for a plastic injection-molded clip that secures a power tool accessory. As the manufacturer had only owned their costing software for a short period of time, the clip served as a good training example and a test of a supplier that was not very transparent in breaking down its bids. Price-versus-cost chart for plastic clip. Shown is the role DFM software plays in supplier negotiations. Image courtesy of Boothroyd Dewhurst, Inc.

Price-versus-cost chart for plastic clip. Shown is the role DFM software plays in supplier negotiations. Image courtesy of Boothroyd Dewhurst, Inc.The company assigned one of its junior engineers to work alongside purchasing to negotiate a price for the clip based upon an initial analysis from the DFM software. The original supplier quote was $3.04. The first DFM estimate done by the junior engineer produced a target cost of $1.44 on an annual volume of 190,000 units. A price negotiation meeting with the supplier created a compromise, based on directional information from the software, of $1.69.

During this meeting, additional material and processing information was provided by the supplier. The estimate was then refined according to improved machine-selection feedback and other software outputs, leading to another downward and final price revision to $1.14 (Fig. 1). That final price resulted in annual savings of $361,000 and a cost reduction of more than 260%. The entire project from start to finish took less than a month, including negotiation and scheduling time amid normal work tasks.

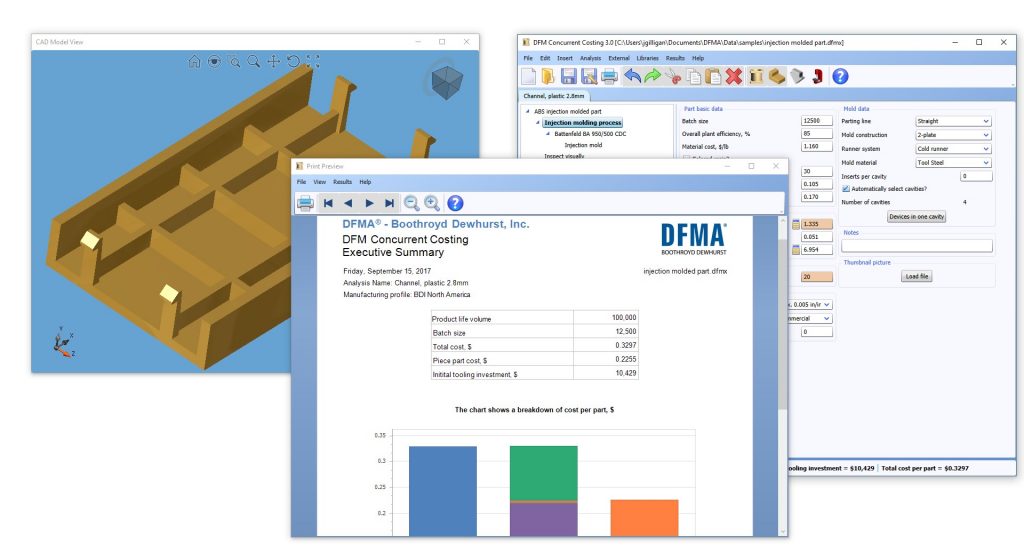

Dynisco Has Costs “Covered”

Dynisco of Franklin, MA, is a maker of extrusion measurement and control equipment for the plastics industry. The company uses Boothroyd Dewhurst, Inc. DFMA software and deploys design for assembly (DFA) and product simplification to ensure that individual components are as elegant and multi-functional as possible.Although cost is an important factor in their selection of suppliers—because the “right” costs also help protect their customers—Dynisco considers speed of delivery, quality and collaboration on design improvement in the mix, too. Recently, to free up internal capacity, the company decided to domestically outsource the manufacture of one of its equipment enclosures, or machine covers. The covers protect and provide visual aesthetics for a melt indexer of plastic material.

A melt indexer measures the melt rate of most types of plastics. Plastic pellets are used in extrusion and injection molding processes. Evaluating both virgin and recycled content is necessary to ensure that material flow and values are up to spec and the molding process is on track. Indexers also prevent material waste. Naturally, these heating and sensor-based systems are protected by enclosures for shipping, operations and general environmental contact. They need to be sturdy, lightweight and affordably made.

Dynisco adheres to a philosophy of continuous improvement and Lean. Each new product cycle or change in manufacture is seen as an opportunity to review a product’s cost, performance status and execution on the factory floor. The indexer covers, now a candidate for outside manufacture, underwent a typical company purchasing and design review. It is one in which suppliers play a role in reviewing and bidding on an existing design or concept, explain their approaches in detail—including machine sequences, setups, fixtures, labor, overhead and more—and make recommendations!

Collaboration Counts

For this project, Dynisco reached out to three suppliers. Discussions opened up immediately about choice of material and the feasibility of certain features. Some new concepts had been developed at the time of the decision to outsource the covers. One was to have wider bend radii at the side corners for aesthetics. Both the DFM software and suppliers called out this feature as expense. It would require new tooling or use of a multi-step sheet approach called bump forming. A bump bend is a series of machine bends “bumped” by the brake press punch a few degrees at a time. There are variables at each bend, just as there are for a single press operation. These differences can stack up, creating errors. The idea was rejected for a standard 1/4-inch bend radii.The existing cover is made from aluminum sheet metal with a power-coated finish. Both steel and two types of aluminum were reviewed, 6061-T6 aluminum for its role in forming stronger (yet more brittle) parts, and a 5052-grade aluminum for its flexibility and common use. The generic, all-carbon steel was passed by for its increased weight. The 5052 was ultimately picked for its universality and for the sake of simplicity in procurement planning.

Sitting together around the software, supplier and customer unpacked the process steps for all alternatives, costing them out in DFM after introducing individual supplier parameters such as machine availability, type and overhead, then seeing the results. Some suppliers had unique approaches for fixtureless welding that were evaluated.

One added discussion was over a machined hole in the cover. “The in-house team had an alternative concept where we cut into the cover to make an opening for the operator interface of a touch screen,” says Matt Miles, product development manager at Dynisco. “Around that width was originally designed a groove that cuts into about a 1/8-in. thick aluminum material, basically putting in this ridge, a kind of chamfer around the entire cutout. The feature was suggested just for aesthetics. That added cost and wasn’t truly needed, and we all agreed it should be dropped. During the same DFM exercise, some mating tolerances in the sheet aluminum were relaxed as well.”

The final indexer cover costs 36% less than in the past, while preserving a 13% profit margin for their supplier. Such savings are exceptional for low-volume products where financial returns are not amplified by high-production accounting. The home factory is freed up for other manufacturing tasks as well.

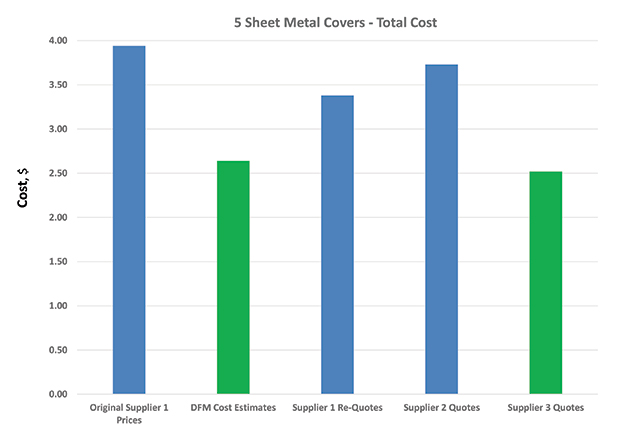

Out of three supplier quotes given Dynisco for manufacture of their indexer cover, the third winning quote (right, in green) was the closest to the original DFM software estimate (left in green). Image courtesy of Dynisco and Boothroyd Dewhurst, Inc.

Out of three supplier quotes given Dynisco for manufacture of their indexer cover, the third winning quote (right, in green) was the closest to the original DFM software estimate (left in green). Image courtesy of Dynisco and Boothroyd Dewhurst, Inc.The Path Forward

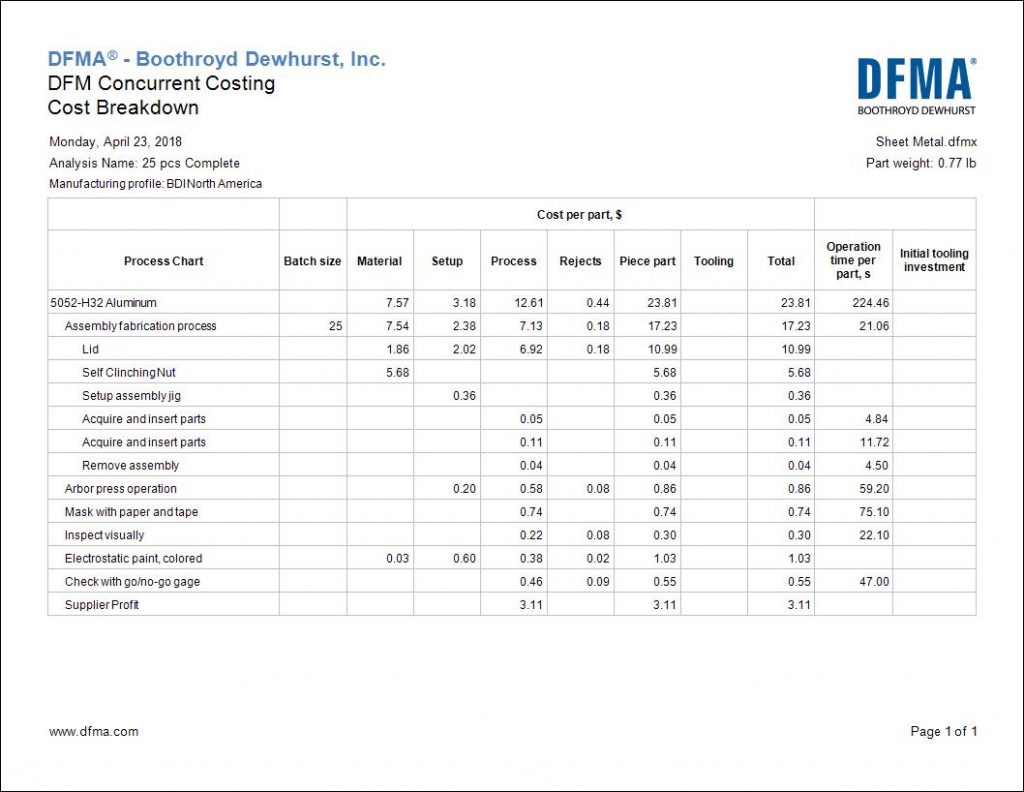

Dynisco is now several years into its DFMA program. Every department of the company and its sister organizations are involved in DFMA design and related procurement practices. Suppliers sit at the table, too. DFM Elements of Cost. The software provides a cost and time breakdown of the material, setup, process, rejects, and tooling (when applicable) required to manufacture parts. Image courtesy of Dynisco.

DFM Elements of Cost. The software provides a cost and time breakdown of the material, setup, process, rejects, and tooling (when applicable) required to manufacture parts. Image courtesy of Dynisco. An example of a DFM assembly fabrication (above) shows how a sheet metal piece becomes a finished, painted part. This cost breakdown captures the assembly process for pressing threaded inserts into the sheet metal piece and then painting the part. A supplier profit translating into 13% is shown within the final ‘should-cost’ estimate. Image courtesy of Dynisco.

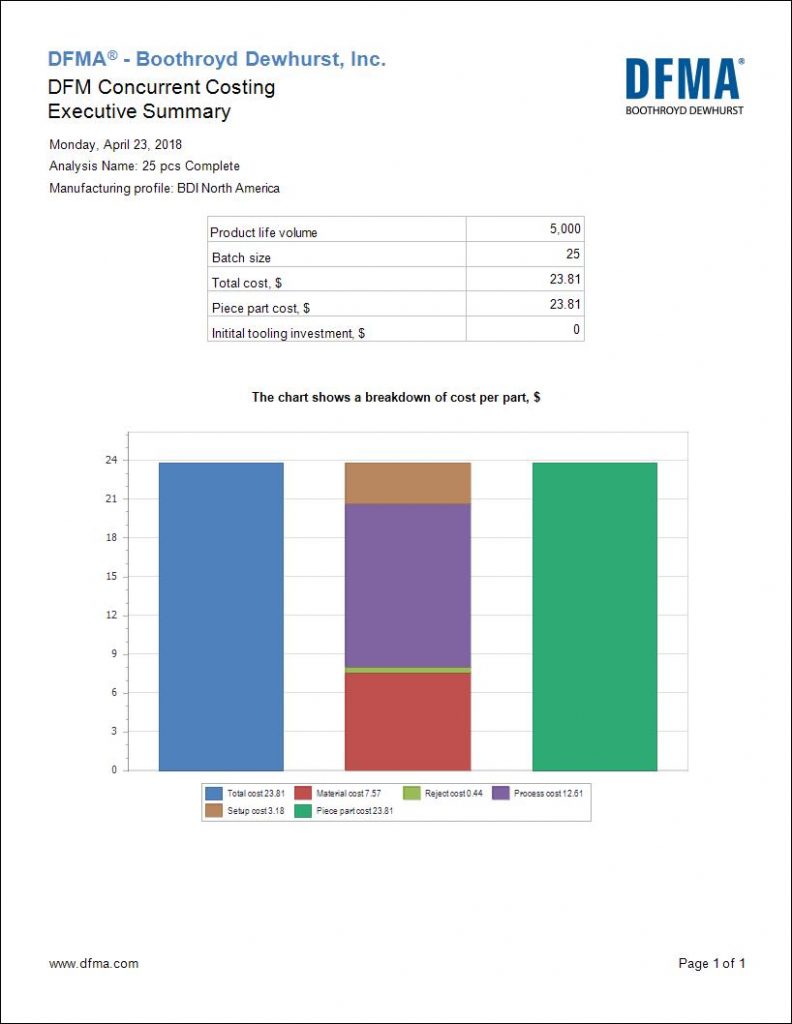

An example of a DFM assembly fabrication (above) shows how a sheet metal piece becomes a finished, painted part. This cost breakdown captures the assembly process for pressing threaded inserts into the sheet metal piece and then painting the part. A supplier profit translating into 13% is shown within the final ‘should-cost’ estimate. Image courtesy of Dynisco. The Executive Summary bar chart exported out of DFM shows a sheet metal part’s cost breakdown based upon the estimated batch size and life volume inputs. Image courtesy of Dynisco.

The Executive Summary bar chart exported out of DFM shows a sheet metal part’s cost breakdown based upon the estimated batch size and life volume inputs. Image courtesy of Dynisco.“Our company doesn’t use the software data as an adversarial approach,” says Miles. “We just show suppliers the root information, where we think we should be cost-wise with DFM. We then invite them to be as competitive as they can. It’s a two-way street though. Dynisco is willing to adjust upwards if that’s called for by solid manufacturing and materials data. DFM is used to share information and brainstorm. In the end, our goal is to create a partnership for managing costs, quality and delivery.”

“This year Dynisco is hosting another offsite executive meeting where members of our supply chain, operations and engineering meet to form a better understanding of the tools that Dynisco and sister companies use,” says John Biagioni, president of Dynisco. “Approaches we have honed such as DFMA, Lean, and total cost of ownership (TCO) are shared openly. This is one of several avenues we take to encourage close partnerships with suppliers—knowing that new opportunities for innovation and cost savings often lie right before us.”

The Business Side of Design

Many in industry recognize that what happens upfront in design carries through to a product’s end-of-life cost and performance. While the focus of Lean Manufacturing for decades was exclusively on manufacturing, greater attention is now being paid to the contributions of design on manufacturing performance throughout all its phases and beyond. Lean is increasingly applied now to administration and every organizational aspect of creating products and services. DFA product simplification and DFM concurrent costing promote Lean, systems-wide engineering and serve as business tools that show the direct financial benefits and consequences of decisions.The costing tools are giving manufacturing engineers, designers, upper managers, suppliers and purchasing departments the means to both evaluate and improve products. Purchasing is the latest discipline to embrace DFM as an integral function. The software bridges the gaps that naturally exist between procurement and engineering—opening another dimension into profitability for manufacturers who can now better understand “price” versus “cost.”

For more info, visit Dynisco and Boothroyd Dewhurst.

Miles Parker is founder of the Parker Group.

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

Image courtesy of Dynisco.

Image courtesy of Dynisco. Image courtesy of Dynisco.

Image courtesy of Dynisco.