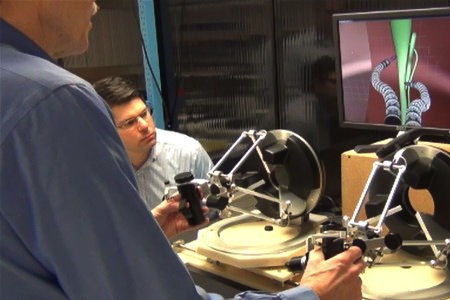

Fig. 6. As the SPORT Surgical System project entered the advanced software-engineering stages, user feedback remained fundamental. At right, Fowler manipulates the master controllers while looking through the 3D visualization system.

April 25, 2014

Robotic surgery has become a widely accepted medical procedure over the past decade, offered by an increasing number of hospitals worldwide (see Fig. 1). The tele-manipulator and software of robotics restore intuitive movement control to the surgeon, providing the right/left hand synchronicity that standard minimally invasive surgery (MIS) lacks.

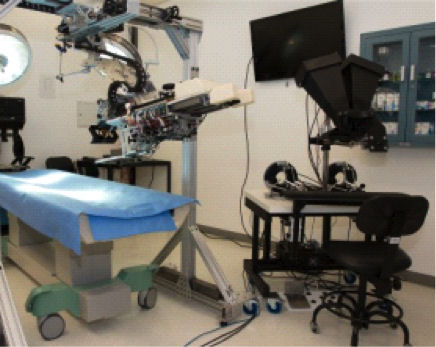

Fig. 1. This operating room mockup scenario shows the robot in left foreground, the single-port entry site with instrument arms performing gallbladder surgery at center, and the surgeon at the workstation in right background.

Fig. 1. This operating room mockup scenario shows the robot in left foreground, the single-port entry site with instrument arms performing gallbladder surgery at center, and the surgeon at the workstation in right background.Growth of sales in life sciences robotics was in the double digits in 2013, according to the Robotics Industry Association (RIA). Global annual medical robotic revenues are currently about $4 billion, and are expected to continue to grow at a 12% annual clip, reaching $19.9 billion by 2019. RIA calls surgical robots “revolutionary tools” for surgeons that help transcend human limitations by providing reduced invasion (less trauma), tremor reduction, repeatability, precision and accuracy.

As a new technology advances, innovative thinking can refine performance. Such was the case for a group of researchers at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons. Seeking to overcome the size, cost and dexterity issues of large, multiple-incision robotics systems, they envisioned a smaller, less-expensive, more nimble device that could perform MIS through a single port of entry into the body, and be moved among operating rooms as needed. The goal was to deliver the advantages of instinctive robotics controls on a compact platform that could be adapted to a wider variety of general surgery operations than is currently available.

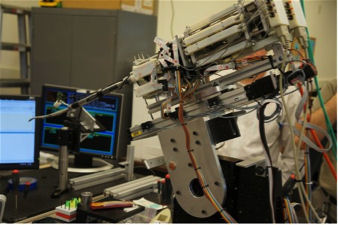

Fig. 2. A concept is born: Columbia and Vanderbilt university researchers had developed their prototype of a single-port robotic surgical tool to this point when the IP rights were acquired by Titan Medical.

Fig. 2. A concept is born: Columbia and Vanderbilt university researchers had developed their prototype of a single-port robotic surgical tool to this point when the IP rights were acquired by Titan Medical.Device developers Titan Medical recognized the opportunities presented by the researchers’ single-port concept, tested the academic prototype (at Vanderbilt University, where one of the inventors had relocated it) and licensed the intellectual property (IP) from both universities. As a public company headquartered in Toronto, Titan has a medical advisory board of leading surgeons as well as partnerships with academic institutions and hospitals around the globe.

“We were already well aware of the complexities inherent to medical device development,” says Joe Talarico, Titan’s VP of business development. “When we decided to explore the potential of this innovative robotic system, the challenges we were facing included manpower, product knowledge expertise, human interface engineering, clinical-regulatory interface, overlap of system and protocol management—as well as subsequent bench, pre-clinical and clinical testing schedules.”

Managing the Complexity of Medical Device Development

When the team decided to try to commercialize the single-port system, Talarico says, “We realized this was not something we could do in-house. We needed one firm that would partner with us to manage not only the physical product development, but also every other aspect of delivering a complex piece of equipment to the marketplace.” That included all the appropriate information for approval from the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) and from the European Union (EU) regulatory agencies.

Fig. 3. Dr. Dennis Fowler, director of clinical affairs for Titan, consults with product development specialists at Ximedica as the university prototype is being developed into a functional system for Titan.

Fig. 3. Dr. Dennis Fowler, director of clinical affairs for Titan, consults with product development specialists at Ximedica as the university prototype is being developed into a functional system for Titan.After considering a number of candidates, Titan chose Ximedica, an ISO-certified, FDA-registered, full-service development firm that focuses exclusively on the medical industry. “We had narrowed our search down to two potential vendors, and ultimately chose Ximedica because of their capabilities, feedback from references, product understanding, communications and management skills, as well as an overall feeling that they could handle all aspects of the project under one roof,” says Titan CEO John Hargrove.

With more than 25 years of experience with medical devices, combination products and consumer healthcare products, Ximedica has a portfolio of clients ranging from lean startups to industry leaders. Projects have included the first-ever wearable sleep monitor, a device for facilitating the delivery of a complex gynecological procedure, an enhanced bedside respiratory system, and a number of novel drug-delivery platforms. Headquartered in Providence, RI, Ximedica was founded by Rhode Island School of Design graduates Aidan Petrie and Steve Lane, and now has offices in St. Paul, Minn., and Hong Kong as well.

Titan engaged Ximedica in the summer of 2012 to bring to life what is now known as the Single Port Orifice Robotic Technology (SPORT) Surgical System. Dr. Dennis Fowler, one of the co-inventors of the licensed technology who is a known thought-leader in the adoption of MIS techniques, worked closely with Titan and Ximedica as a consultant. Now director of clinical affairs for Titan, Fowler is also a professor of surgical science and director of the Center for Innovation and Outcomes Research in the Department of Surgery at Columbia.

Because larger, multi-port robots are usually employed for specialized operations such as hysterectomies and prostatectomies, Fowler and his co-inventors had initially targeted the more straightforward procedure of gallbladder removal (a.k.a. cholecystectomy, which is performed for approximately 1 million people annually in the United States alone). As the complete system takes shape, Fowler points out that the SPORT Surgical System is essentially a platform from which the technology can advance still further.

“Once we have the platform fully developed for cholecystectomy, we can refine it for other general surgeries, such as appendectomies and ear, nose and throat procedures,” he says. “In subsequent generations, we will be able to add additional sensors, tools and software enhancements. But first we need to perfect the platform.”

Under Ximedica’s wing, development of the SPORT Surgical System reached the critical milestones of user-needs research, achieving technical feasibility and live-tissue testing in just 15 months. At press time, the development and building of the pre-production prototype was underway, to be followed by pre-clinical and clinical trials, regulatory submission, and a pilot launch. Initiation of U.S. and outside-U.S. regulatory clearance processes is currently scheduled for 2015, followed by limited commercial launch. Titan is planning to introduce the SPORT Surgical System in Europe and the United States—the world’s two largest markets for robotic surgery.

Planning before Engineering

“This kind of fast, cost-effective design cycle is essential for a new company trying to enter a market with a more efficient product at a lower price point,” Ximedica Co-founder and CIO Petrie says. “But you must start from complete information so that early decisions are made intelligently and accurately. Extraneous, nonessential features in a design can impact engineering and production costs and, ultimately, time-to-market.”

Ximedica began the SPORT Surgical System project by bringing all parties together to visualize the full scope of the challenges that lay ahead. “Before anyone even picked up a pen or started putting together a schematic, we needed to understand every segment—the IP landscape, the clinical procedure, the users, the economics, competitors and so forth,” says Petrie.

Meeting in person with Titan as often as once a week, with daily update phone calls and emails in between, the Ximedica team went to work. Human-factors engineers, information architects, regulatory specialists, and R&D, design, software and mechanical engineers put their heads together with the client. In fact, approximately 60 people have worked on the project to date.

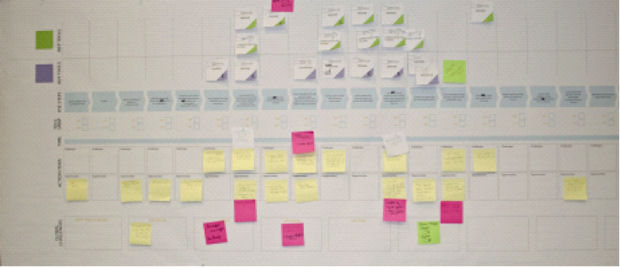

“Ximedica’s proprietary process development and management system marries lean development best practices with the rigors of regulatory requirements to create a smooth path toward commercialization,” says Petrie. To this end, Ximedica’s “Opportunity Assessment Evaluation” examines design, manufacturing, regulatory, market forces, resources, planning, and both client and competitor IP, then identifies associated risks and offers targeted mitigation solutions (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Ximedica’s proprietary Opportunity Assessment Evaluation process considers every aspect of each medical device product development project, identifies risks and offers mitigation options. For Titan Medical’s SPORT Surgical System project, the gallbladder surgery procedure was thoroughly deconstructed (above). Budget remained under plan throughout.

Fig. 4. Ximedica’s proprietary Opportunity Assessment Evaluation process considers every aspect of each medical device product development project, identifies risks and offers mitigation options. For Titan Medical’s SPORT Surgical System project, the gallbladder surgery procedure was thoroughly deconstructed (above). Budget remained under plan throughout.“Risk management is critical in this business,” Petrie says. “Do you know who your competitors are, how long product development is going to take and how much it’s going to cost? It’s our job to accurately forecast, and then answer, every one of these questions as we proceed.”

Ximedica provides Titan with ongoing reports that track time and expenses throughout the project.

Design Begins with the User in Mind

Of paramount importance in medical device design is the user’s point of view. “Medical product development always has to start with the human needs, and work from there into the engineering,” says Petrie. “The human component runs through Ximedica’s DNA due to our design-school origins. Our philosophy dovetails perfectly with the ‘FDA Waterfall Design Process’ [a development requirement for any medical device submission] that begins with user needs.”

Fig. 5. Ximedica team members (foreground) pay close attention to user research on the functionality of the robotic arm portion of the SPORT Surgical System during mock gallbladder surgery.

Fig. 5. Ximedica team members (foreground) pay close attention to user research on the functionality of the robotic arm portion of the SPORT Surgical System during mock gallbladder surgery.So who exactly are the “users” of a robotic surgery system, and what are their needs? The answers go far beyond a primary surgeon sitting at a workstation. The hospital purchasing agent is considered a user, as are the secondary surgeons at the bedside, scrub nurses working alongside the doctors, circulating nurses passing materials into the sterile field and, ultimately, the patient. Obviously, a thoroughly trained, core surgical team is fundamental. But the device itself needs to be designed from the inside out to function in a manner that not only optimally enhances the surgeon’s skills, but also benefits the hospital that buys it, fits smoothly into the OR space and workflow for a particular surgery, and provides the best possible outcome for the patient.

To collect the human data that would be the foundation of the SPORT Surgical System design map, Ximedica conducted rounds of in-person interviews with experienced hospital personnel—both those connected with Titan (like Fowler) and independent individuals. Ximedica also carried out a deep analysis of gallbladder surgery itself, again in consultation with experts.

Users were also asked to try out components of the system in mock-surgery settings. Together, the user and surgical-procedure data informed the choices of the appropriate mix of features for the system, creating a concise product description for design purposes.

“We first defined the steps required to do an operation, then determined every little movement or action that needed to happen at each step,” says Fowler. “Finally, subcomponents of the device were designed to enable each action. Ximedica’s engineers were assigned to develop each subcomponent as needed. The most impressive thing about working with the Ximedica team has been their adherence to process, which was standardized, detailed and meticulous throughout.”

Aligning Functionality with User Needs

The next step was to evaluate the university prototype against the defined user needs, and prepare a “gap analysis” of what was required to align function with those needs. “We used a systems engineering approach to break the challenge down into manageable pieces, and assess the gaps between what the existing device could do vs. what it had to do,” says Ximedica Senior Program Manager Corey Libby.

“There were three critical functional areas that needed to be de-risked, from a technical aspect as well as a manufacturability aspect,” he continues. “Through our design process, we developed a deep understanding of the user’s needs, making it very clear that successful implementation of the SPORT Surgical System must include highly advanced intra-cavity 3D imaging, instinctive control of the robotic components, and extreme dexterity of the surgical instruments. As we progressed toward these milestones, everything had to be in compliance with FDA and EU medical device development requirements.”

Ximedica provided Titan with detailed documentation as each of the technical milestones (instrumentation, master controls and visualization) was achieved.

“When one of our clients has a product undergoing development, good progress demonstrates value to investors,” says Libby. “Titan needed to be able to show their investors where they were at any given moment and, more directly, that they had arrived at where they said they would be in a certain timeframe. Pulling it all together and figuring out how to do it quickly on a tight schedule was Ximedica’s side of the challenge.”

Engineering the Solutions

As the SPORT Surgical System project advanced from planning to prototype production, Ximedica’s 80,000 sq. ft. of laboratory/engineering/product development space swung into action.

To tackle the instrumentation milestone, software engineers began by establishing a kinematic framework to mathematically describe the position and orientation of the two articulating instrument arms that emerge from the device once it enters the patient’s body through the single port.

“Using MATLAB (from MathWorks) enabled us to investigate different instrument designs and configurations very efficiently in the early stages of concept development,” says one Ximedica R&D engineer.

They then developed software systems (based on C++ OpenGL) to control simulated instruments, as well as the motor drives that move them, implementing the kinematics in a real-time environment (see Fig. 6). “We did a lot of development around the controllability, instinctiveness and suitability for intended tasks of the robotic instruments before we ever actually built one,” the R&D engineer says. “We controlled three-dimensional instruments on a computer screen first; it was an efficient tool that fed important information back into development.”

Fig. 6. As the SPORT Surgical System project entered the advanced software-engineering stages, user feedback remained fundamental. At right, Fowler manipulates the master controllers while looking through the 3D visualization system.

Fig. 6. As the SPORT Surgical System project entered the advanced software-engineering stages, user feedback remained fundamental. At right, Fowler manipulates the master controllers while looking through the 3D visualization system.As the instrumentation design solidified, the group wrote additional computer code that would allow the master controllers (held by the surgeon) to manipulate the arms with all the intricate, fine-tuned movements required to perform a surgery (see Fig. 7). Initially conceived with five degrees of freedom (DOF) of movement, the arms were ultimately designed to have seven DOF based on projected clinical and commercial benefits that the SPORT Surgical System could provide surgeons in the future.

Fig. 7. While simulation software dramatically sped up product design, it also provided a side benefit as a training tool for the surgeon. At left, Fowler tests the performance of the master controllers linked to feedback from a simulation of the robotic arms in action, as a Ximedica engineer looks on.

Fig. 7. While simulation software dramatically sped up product design, it also provided a side benefit as a training tool for the surgeon. At left, Fowler tests the performance of the master controllers linked to feedback from a simulation of the robotic arms in action, as a Ximedica engineer looks on.Computer Simulation Supports Product Development

“Computer simulation was pivotal in several important moments of discovery,” says the R&D engineer. “3D modeling demonstrated features that were very hard to visualize and understand without such tools.”

Adds a Ximedica design engineer, “The use of (Dassault Systemes’) SolidWorks’ CAD platform as a developmental tool allowed us to quickly visualize mechanical system interactions so we could virtually prototype concepts for validation.”

“Simulation saved us, and our client, time and money,” says a Ximedica software engineer. “We didn’t have to physically build each design and integrate it into a physical system. Surgeons testing the concepts were able to switch control among several simulated designs within a single study session, giving us a clear outlook as to the path we should take moving forward.”

An important side benefit of the extensive use of computer simulation was the realization that the in-house methodology created by Ximedica could be developed further into a training tool for the SPORT Surgical System. Fowler, who is also medical director of New York Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Medical Center’s Simulation Center, is enthusiastic about this discovery.

“In the process of looking at the animated CAD simulations created for the purpose of trialing different designs of the SPORT Surgical System, it became very clear that this would enable surgical practice as well,” he says. “Simulation is an important tool for training and assessing surgeons’ skills.

“We will encourage hospitals to require a certain level of performance in a simulator before allowing surgeons to work on patients,” Fowler continues. “This is, of course, not up to us; it’s a policy issue. The healthcare system needs to create the mandate and the metrics. But Titan will certainly partner with the hospitals and recommend guidelines for granting privileges in robotic surgery.”

The final technical milestone in the SPORT Surgical System project was the development of a sophisticated visualization system. Down-selecting from multiple potential architectures, testing both virtual and physical prototypes, the team arrived at a final custom “chip-on-tip” insertable camera concept. The high-definition, 3D camera folds into the entry device and then is deployed, once inside the body (along with the two instrument arms), to give the surgeon a direct view of the arms he or she is controlling. The surgeon sees the surgery through a 3D imaging portal at the master control station while manipulating the arms.

AM Provides a Rapid Look at Designs

While computer-aided design tools saved time and money on prototyping, at many points during product development the engineers wanted to prove out their design ideas with real-world examples to assess the user-friendliness—and the eventual manufacturability—of the surgical tools they were creating.

“One of the most challenging design areas was the connection point of a first set of wires to the distal end of the snake-like instrument arms,” says a Ximedica mechanical engineer. “Due to the size limitation imposed by minimally invasive surgery and the component materials required for this design, most conventional joint methods such as screws, welding and bonding were either not possible or their application was severely compromised. From similar-type product benchmarking, we determined that additive manufacturing [AM] would be an effective material forming solution.”

The group produced many proposed solutions to various design challenges via AM using Ximedica’s Stratasys 3D printer. “We did a huge amount of AM prototyping for this project—three to five days per week for the entire 15-month period,” says the mechanical engineer. Their prototyping work will facilitate actual manufacturing once the SPORT Surgical System reaches the production stage, because a number of components will have already been designed for end-use manufacturing with AM.

Meeting User Needs

With all subsystems developed, another round of user research established that the SPORT Surgical System was ready to move into lab testing, and then live-tissue testing. Successful deployment of the complete system was achieved in late 2013. With a regulatory strategy fully drafted, progress continues today.

“Ximedica has provided Titan with a functional prototype that answers what every medical device executive wants to know: Is this product actually going to work?” says Petrie.

The answer to date is a resounding yes, as demonstrated by live-tissue tests in December 2013. Notes Titan CEO Hargrove, “Ximedica has been a tremendous partner for Titan. They have done a great job of managing our development, and their accountability has been prevalent every step of the way.

“A good partnership can mean much more than just a good contract relationship,” he concludes. “It can also mean support in managing the extraordinary changes in both vision and actions being demanded of all of us in this industry today.”

More Info

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

About the Author

DE’s editors contribute news and new product announcements to Digital Engineering.

Press releases may be sent to them via [email protected].