This Bunkspeed render visually represents the process of converting 3D engineering data into a visually appealing marketing image.

September 1, 2014

This Bunkspeed render visually represents the process of converting 3D engineering data into a visually appealing marketing image.

This Bunkspeed render visually represents the process of converting 3D engineering data into a visually appealing marketing image.In the grand scheme of things, animation of any kind is a relatively new capability for engineers. Many of you will still remember a time, not all that long ago, when most designs were drafted by hand on paper and rendered with ink and paint.

Today, engineers use CAD more often than not, and you will find some form of animation capability in virtually every CAD product, be it AutoCAD, Inventor, SolidWorks, Solid Edge, Rhino or something else. The extent of the programs’ animation capabilities differ, but you can at least create simple turntable animations, and probably do lighting or sun studies. The animation capabilities of the heavyweights extend to the ability to animate fully articulated assemblies, such as internal combustion engines, or caterpillar treads powered by virtual gears, springs, motors and physical forces.

Why Third Party?

Given that you can almost certainly do animation within your CAD program itself, why bother to involve outside programs? There are a few reasons, but chief among them would be ease of use, render quality and speed.

There’s a constant state of war between power and ease of use. Sometimes, a package capable of accurately animating an entire powertrain isn’t the best choice for doing simple turntable animations. And while all professional CAD packages will produce some kind of animation, it might not be the best looking or the fastest to render.

Bunkspeed and KeyShot

Consider a pair of applications: Dassault Systemes’ Bunkspeed and Luxion’s KeyShot. Without getting into the details of which program has the better feature implementation or the faster rendering engine, I’ll just say that the two programs are clearly going after similar markets: people in search of fast, easy, photorealistic renders of their geometry. It’s just flat-out easy to get a gorgeous render out of either application.

Both take advantage of high dynamic range (HDR) lighting where you use a photo of your intended environment and the application derives realistic lighting from that photo. The programs give you photorealistic radiosity, reflection, refraction and caustics. The final results are fit for a magazine beauty shot or a boardroom presentation. And they are very, very fast.

Both programs also support animation, which is kept as simple and intuitive as possible. The simplest animations—such as turntables—are accomplished in just a few steps, via wizards. For more control, there’s a timeline where you can drag key frames around. You can animate an entire model, or selected parts of a model. You can animate materials and lights. You can, for example, open up a car’s door to show the interior, or simply fade the door away to transparency. You can change a car’s paint job from red to green to shiny metallic blue. You can turn the headlights on and off. Both programs let you link parts together hierarchically to achieve more sophisticated animation.

Still, there’s a limit to the complexity you can achieve in programs such as Bunkspeed and KeyShot. If you need beautiful renders as well as complex articulation, relationships or inverse kinematics, and your CAD environment doesn’t provide it, you’ll have to import your model into another application, such as Maya, Max or modo, that’s designed for that kind of work.

Import Necessities

Because you can’t create anything but the most basic shapes in KeyShot or Bunkspeed—planes, cubes, spheres and so on—it’s clear that your geometry will be coming from somewhere else, most likely a CAD application. To that end, both KeyShot and Bunkspeed can import from all the major CAD file formats (CATIA, AutoCAD, Rhino, SketchUp, SolidWorks, Solid Edge, Parasolid, OBJ, etc.).

For even tighter integration, KeyShot’s LiveLinking technology allows the program to run alongside SolidWorks, Creo and Pro/E, where it can be updated in response to geometry or material changes with a single click. Bunkspeed uses a similar technology to integrate with SolidWorks.

Real-time Visualization

Real-time rendering is something of a misnomer. Exactly how close you come to real real-time depends both on your workstation and on the amount of geometry jammed into the program. But what about an insanely complex model such as a modern automobile, comprising tens of thousands of parts and tens of millions of polygons? That brings you to the special domain of Deltagen.

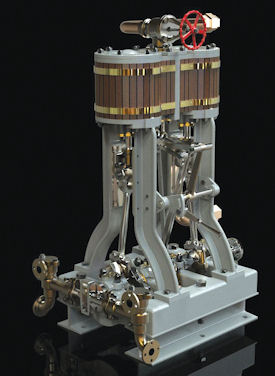

An 1879 twin cylinder steam launch engine, modeled in SolidWorks and rendered in KeyShot by Bill Gould.

An 1879 twin cylinder steam launch engine, modeled in SolidWorks and rendered in KeyShot by Bill Gould.The Deltagen application specializes in near real-time visualization of big, complex data sets. I wrote in a previous issue about then-RTT demoing Deltagen at SIGGRAPH 2013, where they pulled in an entire Nissan Pathfinder—more than 40 million polygons worth of data—with the help of a 12GB NVIDIA K6000 graphics card. With minimal cleanup and preparation, Deltagen was able to create a scene with high visual fidelity, running on a workstation in real time, with full global illumination. They could move the camera inside, outside or under the hood; the whole model was there.

RTT was recently acquired by Dassault Systemes, and has been re-branded 3DXCITE. Dassault already owns heavyweight CAD applications CATIA and SOLIDWORKS and, with the RTT acquisition, also adds the above-mentioned Bunkspeed to its stable. Expect all these products to become ever more tightly integrated.

Looking Ahead

CAD animation is getting faster, better looking and cheaper. As a consequence, animation is becoming available further forward in the design process. We’ve seen the same thing happen with 3D, finite element analysis, still rendering and more. Near real-time rendering is becoming common, which means more people are doing more renders, earlier in the design process. Expectations of graphic quality, consequently, keep going up.

Real-time rendering technology will have an even greater effect on animation, which requires orders of magnitude more rendering. It doesn’t make sense to do animation tests early in the design process if they’re going to take a few hours to render, for example. On the other hand, it might make a lot of sense if they only take a few minutes—or better yet, a few seconds.

How about big model rendering, as exemplified by Deltagen? While few of us will ever have occasion to fit an entire car into our CAD application of choice, we always seem to find a way to use whatever capability is available. The ability to work with ever-larger models can mean significant times savings that would otherwise be spent cleaning up and optimizing models before animating and rendering them.

More Info

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

About the Author

Mark ClarksonContributing Editor Mark Clarkson is Digital Engineering’s expert in visualization, computer animation, and graphics. His newest book is Photoshop Elements by Example. Visit him on the web at MarkClarkson.com or send e-mail about this article to [email protected].

Follow DE