Latest News

August 27, 2012

Daniel Wilson, a dinosaur-obsessed Indiana boy, has a name for his arm. He calls it Pinchy. It isn’t the arm he was born with; it was custom-designed for Daniel by two biomedical engineering students from the Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. Pinchy is Daniel’s second arm, which straps onto the original. Outfitted with Pinchy, Daniel can do something other boys take for granted. He can ride a bicycle.

Daniel, like his great-great uncle, was born with an arm that’s shorter and smaller than yours or mine. He suffers from what’s medically called “longitudinal deficiency.” Because he has only limited reach and grip, he cannot do what comes naturally to other boys, like dangling from a monkey bar or swinging a baseball bat.

One day, Daniel’s mom Emily caught sight of a headline in the newspaper: “Rose-Hulman Students Developed Prosthetic Arm.” With Daniel’s consent, his mom contacted the school. A few weeks later, in September 2011, two Rose-Hulman students, Mark Calhoun and Jacob Price, came knocking on the Wilsons’ door.

“[Disability] is not a subject you want to bring out as soon as you first meet someone. We weren’t sure how to approach it. So we were being gentle with the subject,” recalled Jocob. But Daniel’s sense of humor broke the ice. The boy demonstrated how easy it was for him to slip out of a standard pair handcuffs with his slim arm. “See, I could never get arrested,” he proclaimed.

At Rose-Hulman, senior-year bioengineering students traditionally undertake a real-world design project. Like Mark and Jacob, many of them participate in the initiative that pairs them up with someone in need of a prosthetic. Rose-Hulman’s corporate supporters include Siemens PLM Software. The school received $27.8 millions’ worth of software donation from Siemens last year, according to Bill Boswell, senior director of partner strategy at Siemens PLM Software. In their freshman years, both Jacob and Mark had been introduced to Siemens’ Solid Edge CAD software, part of Siemens’ Velocity Series.

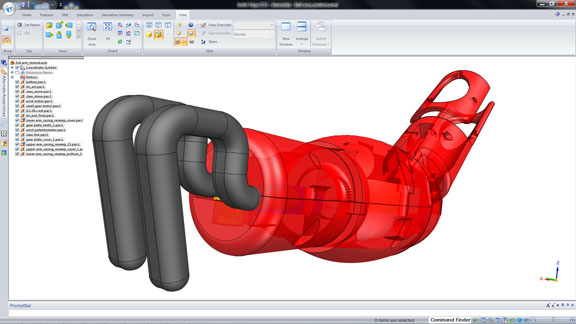

Pinchy was designed in Solid Edge, with input from Daniel. The boy specified red as his favorite color. The strap-on attachment was his idea too. He rejected design concepts with a claw-like gripper and a three-finger gripper. Instead, he chose a dual-hook gripper.

“A lot of the printing of the part [in 3D printing machines] was made easy because we could make what we wanted to make in Solid Edge and save it as STL file for the rapid-prototyping machine,” Jacob explained.

“One of the biggest challenges was to figure out how [Daniel] would control the arm’s operations,” noted Mark. “Because if he cannot control it, there’s no point in wearing it.”

The use of 3D digital prototyping allowed the students to make sure they had sufficient clearances in their design to accommodate the electrical subsystems that would drive Pinchy’s movements. In the design process, Mark and Jacob had to experiment with the placements of several fasteners. In one early prototype, the protruding edges of the fasteners left visible marks on Daniel’s arm, leading the students to conclude placing the fasteners at an angle was a better choice.

The flexibility of Solid Edge’s Synchronous Technology allowed such changes to be made swiftly. “We were able to revise [the fasteners]. We placed them at an angle, with counterbore holes. That made it much more comfortable for him,” said Mark.

The prototypes were sent to a 3D printing technician at school, who helped produce them as ABS plastic parts. Though Pinchy was custom-made for Daniel, Mark and Jacob feel that, with minor adjustments in the harness’ fit and the buttons’ placement, the same design could be used for patients with similar limbs.

With inexpensive modeling software and 3D printing, it’s getting easier than ever to manufacture one-of-a-kind robotic prosthetics like Pinchy. This raises the possibility of a new kind of humans (bionic men and women, if you will), equipped with artificial limbs that can potentially outperform ordinary human capacity.

“Technology helps us make our lives better, but just because we can do something doesn’t mean we should,” noted Mark. Take the case of a solider returning home from battle with a missing limb, he pointed out. “Do I think we should make him a new arm? Yes. Should it be stronger [than an average arm}? Not necessarily. A stronger mechanical arm could potentially be a safety hazard.”

Daniel received his robotic arm this May. His latest photos emailed to the Rose-Hulman students show him proudly wearing his arm. Mark and Jacob fondly remember the cake balls Emily made for them during their visits to the Wilsons’ Indiana home.

Elizabeth, Daniel’s precocious sister, observed, “[Pinchy] wasn’t just a prosthetic. It meant so much more to Daniel than we can even imagine. He’s always willing to try something new. It was very cool to be able to see that side of him.”

Pinchy doesn’t make Daniel stronger than other boys. But it gives him enough reach and grip to ride a bike.

For more watch the video below:

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Kenneth Wong is Digital Engineering’s resident blogger and senior editor. Email him at [email protected] or share your thoughts on this article at digitaleng.news/facebook.

Follow DE