Some team members from RespiraWorks began assembling an early prototype of their ventilator. Image courtesy of RespiraWorks.

July 31, 2020

In the early days of the COVID-19 crisis, as hospitals in the hard-hit U.S. East Coast struggled to cope with a spike of patients with respiratory problems, the alarming ventilator shortage came to light.

On March 24, during his daily live briefings on the crisis, New York Governor Cuomo said, “FEMA [Federal Emergency Management Agency] said they’re sending 400 ventilators. Really? What am I going to do with 400 ventilators when I need 30,000?” (“Cuomo says NY needs 30,000 ventilators, pleads with feds for help,” The Hill).

The crisis has spurred several leading carmakers into action. GM and Ford reconfigured their manufacturing lines to begin producing ventilators. In the private sector, maker communities, 3D systems suppliers and tech firms launched into action to design and deliver rapidly deployable ventilators.

This environment gave birth to CoVent-19 (also dubbed Innovate2Ventilate), a ventilator design challenge hosted on the GrabCAD community and supported by Stratasys. It came online on April 1, and is now entering Phase II, where the seven finalists are expected to begin developing working units and prototypes of their designs.

A Different Kind of Ventilator

On April 17, GM and its partner Ventec announced the first delivery of their ventilator called VOCSN V+Pro, made in GM’s plant in Kokomo, IN, to Franciscan Health Olympia Fields in Olympia Fields, IL, and Weiss Memorial Hospital in Chicago. This is a hopeful sign that industry leaders and manufacturers are stepping up to meet the challenge.

Dr. Richard Boyer, Massachusetts General Hospital Department (Mass General), Anesthesia, is the founder and director of the CoVent-19. He foresees the need for a different kind of ventilator that specifically caters to the COVID-19 crisis.

“Typical ICU [intensive care unit] ventilators cost about $30,000-$60,000. They are not simple devices. They have many flavors of ventilation, some of which may not be needed by a COVID-19 patient. For the challenge, we’re looking for a ventilator that produces one or two types of ventilation specific to COVID-19, not everything under the sun,” he says.

The CoVent-19 Challenge, therefore, does not seek to replicate commercial ventilators in function and scope. Rather, it’s supposed to create a much simpler device, purpose-built for COVID-19 patients. Due to the device’s simplicity, Boyer believes designing, prototyping and getting approval should be comparatively easier. The targeted per-unit cost of production is around $2,000-$3,000.

“The threat [of the ventilator shortage] is still out there, especially outside the U.S.; ventilators will still be needed in future waves of COVID-19,” Boyer says. With experts predicting a spike in infection as the states reopen, such affordable ventilators could be part of the medical community’s strategy to deal with the second and third waves of COVID-19.

Stratasys and GrabCAD

GrabCAD, the online community that hosts the challenge, is part of Stratasys. The portal grew out of a 3D content-sharing and collaboration space. It was acquired by Stratasys in 2014. Currently, GrabCAD is the online destination featuring collaboration software (GrabCAD Workbench), work order management software and 3D print preparation software.

“We were involved with the challenge since its inception,” said Scott Drikakis, healthcare segment leader, Stratasys Americas. “We have more than 7 million active users on [the] GrabCAD community, so we hosted the challenge and promoted it there in the first stage. In Phase II, we are offering design services through our company and the Stratasys Direct Manufacturing division. Each team is working with an engineer of ours.”

RespiraWorks

Ethan Chaleff, an engineer with a background in advanced energy, recalled discussing the ventilator shortage with his acquaintances in the health care and technology sectors during the early phase of the pandemic.

“We had a Slack channel, where we discussed how we might approach this problem and what we might do,” recalls Chaleff. “My friend Edwin Chiu is an engineer. He has parts lying around in his house since we had worked on similar parts. So he decided to put together a prototype as fast as possible.”

Chiu has designed the engine controller for the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket and the electrical controls of the DeepFlight Super Falcon submarine. Eventually, Chaleff, Chiu and other like-minded people from their network became a nonprofit (501C status pending), operating under the name RespiraWorks.

The organization’s goal is “to create a ventilator that can be built and deployed globally,” states its website. “We’re hoping to create something with usage that lasts beyond the pandemic,” says Chaleff. The design submission from RespiraWorks is one of the finalists for the CoVent-19 Challenge.

“Research was easy under the lockdown,” recalls Chaleff. “But as we got into implementation, it’s been challenging. I have access to a workshop with equipment, so we get things delivered there, but I’m not the engineering lead. [To accommodate the geographically dispersed team] we had to buy duplicate equipment and kits so everyone in engineering has a copy of the design to tinker with. Ideally, everyone would look at the same prototype in the same space.”

The digital twin—a dynamic systems model—is useful for research, but at some point, “we have to get people to put on masks, come to a workspace and put the prototype together,” Chaleff says.

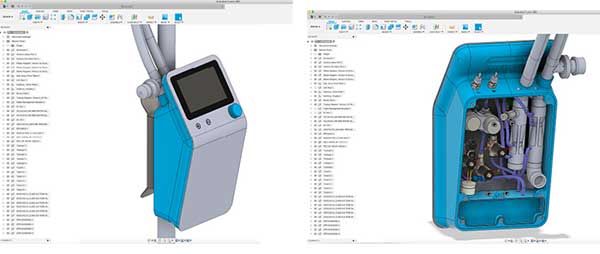

The team used Autodesk Fusion 360, with free licenses provided by the Autodesk Foundation. “It’s a pneumatic system with lots of flexible piping connections. Fusion is helpful in helping us figure out the package, to understand if we have enough room left for PCB (printed circuit boards) or if we need a different case, and so on. To answer these questions, we can all look at the digital model in the software at the same time,” says Chaleff.

System simulation was done using a 1D schematic with pneumatic and mechanical solvers, authored in Modelon Impact, a collaborative design software. “There aren’t a lot of stresses on the design, so we weren’t doing FEA (finite element analysis),” Chaleff explains.

3D printing has been helpful in the prototyping phase, but for mass production, injection molding could be more viable, Chaleff reasons.

fuseproject

Another finalist entry dubbed the InVent Pneumatic Ventilator came from San Francisco-based fuseproject.

“We’re used to working with startups. In these situations, we have to bring teams together very quickly—engineering, legal and management. So within a month, we had solutions to present,” says Yves Behar, founder and CEO of fuseproject.

Ventilator design was new territory, so the team conducted interviews with health care experts to understand what works and what doesn’t.

“One thing that became clear to us in our talk with the health care professionals was that space is very valuable in the ICUs,” notes Daniel Zarem, senior industrial designer, fuseproject. “That led us to design a ventilator that can hang from an IV pole, without the need for a separate stand or a large footprint. The screens and the knobs are designed to be familiar to the doctors and nurses, because they wouldn’t have time to learn a new UI [user interface] or software in the middle of a pandemic.”

The fuseproject team relied on multi-material 3D printing to incorporate 3D-printed gaskets into the ventilator housing. They also relied on multicolor printing to include icons that clearly identify tubes and connectors for easy assembly.

“We used an app called Miro [for virtual collaboration] in the same way we would use a whiteboard in our studio, so everyone has the same view of the project,” recalls Zarem. “To design the geometry, we used Autodesk Fusion 360, SolidWorks and a few other ECAD packages to visualize the circuits and diagrams to validate our design. We passed along STEP files so everyone can open the 3D model.”

Fuseproject, too, sees its design outliving the current pandemic. “Because of the breadth of features and sensors in our ventilator, we see its use beyond the current crisis, in resource-limited places like Africa, for example,” says Zarem.

Winner Announced

Three months after the challenge’s launch and 200 entries later, the CoVent-19 organizers announced on July 1st that the SmithVent, an entry from the 30-person Smith College team, was selected as the winner. According to the announcement, the SmithVent is “one-tenth the cost of traditional ventilators, combines economical proportional solenoid valve technology with an air-oxygen mixing chamber to meet the full set of requirements for COVID-19 ventilation … [and can be made from] readily available, off-the-shelf components.”

InVent by fuseproject and Cionic was recognized as the second-place winner, and the entry from RespiraWorks as the third-place winner. The three winners will receive a total of $10,000 in credits from Stratasys.

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

About the Author

Kenneth Wong is Digital Engineering’s resident blogger and senior editor. Email him at [email protected] or share your thoughts on this article at digitaleng.news/facebook.

Follow DE